Brandon Steiner, in Deal With Yankees, Is a Sports Memorabilia Maven

Brandon Steiner’s mind was churning as he watched the groundskeepers carrying their rakes off the Yankee Stadium infield.

“I can sell those,” he said. “I can put a plaque on them and have Derek sign them.”

What Yankees fan, he asked, wouldn’t want to gather fallen leaves or clear a garden with the rakes that once smoothed the dirt on whichDerek Jeter roamed?

The idea sounded absurd; Steiner would be the first say no one else could have conjured it. But that type of epiphany is the essence of his business.

Steiner has long dealt autographed bats, balls, uniforms and photographs, the stock in trade of the multimillion-dollar sports memorabilia industry. His ability to see a deep fan-athlete connection in even the most overlooked items has made him an outsize figure in the business and a key figure in the selling of Jeter’s final season with the Yankees.

Long before Steiner, 55, conceived of selling the rakes, he built the market for Yankee Stadium dirt itself. When he realized he could sell used bases for hundreds of dollars apiece, he persuaded the Yankees to change their bases several times a game — and home plate at least once every homestand — so he could sell them, too.

“Pre-Steiner, we had two sets of bases for the season, and we’d repaint them and put them back on the field,” said Scott Krug, the Yankees’ chief financial officer. “Now we use at least three sets a game.”

Jeter signed many of those bases, and many other artifacts, as he became the central athlete in Steiner’s business. When Jeter was on a path to 3,000 hits, Steiner masterminded much of the merchandising. He has a similar role for Jeter’s final season, a year after managing the sales of collectibles during Mariano Rivera’s retirement tour.

Before the season, Steiner published a 62-page Jeter catalog, and fans now can buy items like his shoes, his caps and the balls he throws to first base. But the catalog also includes several photos of Steiner with Jeter that give the marketer the aura of being something he is not: a Yankee. It is an aura that Steiner eagerly promotes.

Creating Collectibles

The modern memorabilia industry sprang largely out of fans’ beseeching ballplayers for autographs on scraps of paper that were more likely to be treasured than sold. The hobby transformed into more of a business in the 1970s after stars like Willie Mays, Hank Aaron and Mickey Mantle retired and demand grew for their signatures on anything they might have used or touched, said Tom Bartsch, the editor of Sports Collectors Digest. Conventions and shows soon proliferated, giving more fans willing to pay a little extra a chance to meet players. Auction houses got into the game, selling not only rarities like Babe Ruth’s bat and Lou Gehrig’s uniform but also Shea Stadium’s hot dog grills.

Steiner Sports may not be the biggest company in this industry — Fanatics Authentic, Tri-Star Productions and Upper Deck Authenticated are among his major rivals — but Steiner is certainly its most prominent executive. He and his company sell a familiar range of signed memorabilia and a subset of high-priced, created collectibles that have become his specialty: salvaged items like lineup cards and rosin bags; autographed seat backs; and mixed-media collages that often include a piece of used equipment with a photo of it in use.

“I think at the highest level of consciousness,” Steiner said dreamily one day as he discussed his approach to designing his products. “I always thought I was a little weird.”

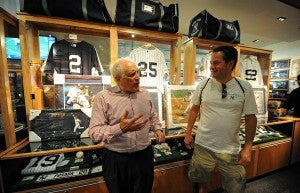

During a tour of his headquarters in suburban New Rochelle, N.Y., Steiner enthusiastically walked the two-story, 45,000-square-foot warehouse, past its racks of Yankee jerseys and warm-up jackets and stacks of bases, home plates and pitching rubbers. There was a box of broken hockey sticks, repurposed as backscratchers, and a table on which discs of stadium dirt from around baseball were piled like poker chips.

Yankee clubhouse swivel chairs, once sat on by players and now available for hundreds (and sometimes thousands) of dollars, awaited buyers.

Peering into a box of unsold Chicago Cubs goods, he said, “We did a Cubs deal that was a disaster. The team just never got better.”

Steiner stopped regularly to admire his company’s handiwork. Three times he gestured to an item — one of them a Jeter shadow box containing a batting glove mounted over an image of it on Jeter’s hand — and declared, “That’s vintage Steiner.”

The Jeter Connection

A child of Brooklyn, Steiner has a personality that alternates between exuberant archivist and scrappy hustler, and while he has deals with several teams and colleges and dozens of players in other markets, he relentlessly markets the Yankees to anyone willing to pay as little as a few dollars or as much as $25,000 for a product. His profile is fueled by the self-promotion he has been known for since the early 1990s, when he hosted radio programs at sporting goods stores, arranged athlete appearances and became a sought-after commentator on sports marketing.

Back then, he impressed athletes like the Rangers’ Mark Messier and Mike Richter with his ability to find moneymaking opportunities for them that required little effort. “I was shocked to hear someone say, ‘Sit on your rear end, sign autographs, and I’ll pay you,’ ” Richter said.

He saw Jeter’s value early, pursuing him — and his agent, Casey Close — at a dinner for Jeter’s Turn 2 Foundation in 1996, Jeter’s first full season with the Yankees.

“I was there to get in front of anybody named Jeter or Casey,” Steiner recalled. He met Close and Jeter’s father, Charles; a few months later, he met Jeter, and got him some early signings. A one-year deal with Jeter in 1998 led to a three-year contract in 2000 that Steiner said was worth $5 million.

Jeter is as essential to Steiner’s brand as he has been to the Yankees’ throughout his career. No single athlete, among the many across various sports, has had a bigger impact at Steiner Sports, financially or for its image. On Sunday, the Yankees will celebrate Jeter’s career before the Yankees’ game against Kansas City.

Yet it was Steiner’s joint-venture agreement — a deal Steiner completed in 2004 only after assuaging the former owner George Steinbrenner’s doubts about him and the fraud-filled memorabilia market — that sealed Steiner’s connection to the Yankees. The contract led his parent company to provide the capital he needed to pay New York City $11.5 million for the rights to raze the old Yankee Stadium in 2009 and sell its contents, and about $6 million more in demolition, seat removal and insurance costs. He has done his best to monetize everything: seats, turnstiles, even pieces of the stadium’s concrete structure beyond the outfield, which he had repurposed into tiny stadium replicas when the pieces proved too large to sell intact or in big chunks.

Steiner said he inherited his entrepreneurial spirit from his mother, Evelyn, who ran a beauty parlor on Kings Highway but earned too little at times to avoid needing food stamps while raising her three sons. When she was hospitalized for obesity-related illnesses, young Brandon shopped and paid the bills.

“My mother knew he’d be successful,” said Steiner’s younger brother, Adam. “She would say: ‘Brandy, I never have to worry about him. His eye is on the ball.’ ”

His father left less of a mark. Irving Steiner took Brandon, his middle son, to his first Yankee game but did not play catch with him.

“There were only nine people at his funeral,” Steiner said of his father. “I’ll never have just nine people at my funeral.”

Steiner’s drive to succeed seems like a full-throated reaction to his father’s anonymity. As he walked through Yankee Stadium during a recent game, he looked like a mayor chasing votes. He greeted ushers and waiters and schmoozed with friends like Mitch Modell, chief executive of the Modell’s sporting goods chain, and the former Yankees relief pitcher Jeff Nelson, who was in the stands with his family.

In his stadium store, Steiner, stocky and silver-haired, stood available for nearly a half-hour to anyone wanting to know the value of a piece of memorabilia, and at one point he promised an 11-year-old boy a gift of Jeter goods if he improved his grades. When one of his employees told him that someone had purchased one of the bases that he had witnessed being removed at the end of third inning, Steiner hand-delivered it to the buyer, an executive with FedEx.

And when Jeter turned his gaze from the on-deck circle in the late innings, he saw Steiner sitting behind home plate.

“You’re everywhere, man!” he shouted above the crowd’s noise, an affirmation of Steiner’s zeal and a validation of his connections.

Deals Gone Sour

Steiner has built his company into one with about 90 full-time employees and around $50 million in revenue, but it has been owned since 2000 by the giant marketing conglomerate Omnicom, which paid around $30 million to add it to a stable which includes advertising firms like BBDO.

Steiner had, by that point, fueled his memorabilia business by signing dozens of players in various sports to contracts, still a mainstay of his company.

“I don’t think there’s any luck with him,” said Randy Weisenburger, the chief financial officer of Omnicom. “His mind is going 24/7 about the business; it’s just the way he’s wired.”

Steiner’s riches enabled him to build a nearly 17,000-square-foot house in Scarsdale, N.Y., for his wife, Mara, and his 23-year-old son and 20-year-old daughter. It has an indoor basketball court and a single bowling lane, he said, to commemorate a sport he played with his father.

In one vast room is Steiner’s personal collection of memorabilia, including an armoire filled with trading card sets; a stack of old issues of Sports Illustrated; Rivera’s cleats and outfield shagging glove; and an old Shea Stadium ticket dispenser that Steiner said contained the stubs to every game he had ever attended. From several drawers he pulled out albums filled with letters of gratitude from sports figures like Billie Jean King and Lou Holtz, and Joe Torre, and photos of him with myriad stars.

“Not bad for a kid from Brooklyn,” he said as he flipped the pages. It is one of his favorite refrains.

His success has come with criticism. He has sued some clients for failing to meet their obligations and been sued by others, accused of not meeting his. Most were settled quickly or dismissed. He explained that he does not want the publicity of a trial or extensive discovery if he can end litigation quickly, saying, “I’m part of a big company, and I’m partnered with the Yankees.”

While none of his competitors would provide extensive details about their dealings with Steiner, and preferred not to speak on the record, some privately said that he was a relentless competitor too dependent on his Yankee business and that he pushed hard to dominate his markets. Steiner denied that he wanted to overwhelm his rivals but he freely conceded: “The rap on me is I’ll do anything to win. I’ve probably calmed down. I won’t do anything at all costs.”

Still, he said, some of his rivals were envious of him and his influence in the industry. Some also do business with him and he with them.

While Steiner’s Yankee connections have produced an unquestioned success, he has not been able to replicate that with other teams. His Mets contract unraveled amid rancor with Jeff Wilpon, the team’s chief operating officer; Steiner said he was happy it ended. Deals with the Mets, the Cubs, the Dallas Cowboys and the Los Angeles Dodgers did not last long or soured. His venture with the University of Alabama ended, and a recent one with Notre Dame is phasing out. His agreement with the Boston Red Sox — one that is memorialized in a team-signed Champagne bottle from the 2007 World Series championship — ended because of a conflict with another vendor. The team also would not let him remove and sell home plates from Fenway Park.

“I was heartbroken that that ended,” he said.

Today, Steiner’s remaining deals are with Syracuse University, his alma mater; Madison Square Garden; and the Nets. But the Yankees remain his primary meal ticket.

“He doesn’t sell any of our dirt,” said Marc Donabella, Syracuse’s associate athletic director. “We play on artificial surfaces. But he has sold pieces of our court.”

A Locker Tussle

Steiner is a devoted Yankee fan who believes he has the refined tastes to satisfy fans like himself. Yankee executives regard him as a bit of a creative eccentric who brings them profits from selling products that perpetuate the team’s branding, even if they sometimes shake their heads at what Steiner deems collectible.

Randy Levine, the Yankees’ president, recalled, with a laugh: “He took the furniture from my old office, from Cash’s old office and George’s old office and he sold it,” referring to Brian Cashman, the general manager, and Steinbrenner.

He added: “He pushes us, but when we say no to him, he backs off.”

Jeter said he has not had to push back against ideas from Steiner, who he said knew what not to suggest. Nonetheless, Jeter likes to needle Steiner. After the Yankees’ home opener in April, Jeter was asked which keepsakes of his final Yankee Stadium opening day he would take with him.

“Brandon Steiner takes everything,” Jeter said. “I’m good taking the win. Steiner Sports has the rest.”

Jeter teased Steiner about the difficulties he faced getting his old Yankee Stadium locker from Steiner, saying their relationship nearly ended over it.

“Brandon didn’t want to give it to me,” Jeter said. “That’s true.”

Steiner would later say that it was expensive to remove and ship the surprisingly heavy locker and difficult to fit into Jeter’s house in Tampa.

The resolution, he said, did not involve Jeter paying for it. “We worked out a trade,” he said. “He’s fair.”

Steiner is on his third contract with the Yankees, to whom he pays an annual rights fee — one that he and the team would not reveal — and a share of Yankees Steiner Collectibles profits. He sets prices that conform to the Yankees’ immense popularity and the demand for their goods, whether it isa ball, a clubhouse swivel chair or a coach’s used equipment bag. Virtually anything that anyone in pinstripes has touched or played in is for sale — from Jeter’s used uniforms (more than $25,000, dirt stain included) to a locker once occupied by a batboy nicknamed Wonz to the 2013 spring training locker nameplate of Kyle Higashioka, a Yankees’ minor league pitcher ($110).

Charles O. Kaufman, the publisher of Sweet Spot, a memorabilia newsletter, said that Steiner benefited immensely from his association with a high-end brand like the Yankees, but that “the organized collecting public knew that Steiner Sports offered signed memorabilia and other gear at well-above market prices.

“Collectors often feel ripped off, but buy anyway,” Kaufman said, admitting, “People shop with their pocketbooks, not their brains.”

One evening in late June, more than 900 people crowded the 92nd Street Y’s auditorium for a Steiner event starring Jeter and Tino Martinez. The show combined star power, exclusive memorabilia and his creation of premium packages for fans who want not only to pay to hear their favorite athletes speak but also to pay even more for a more intimate brush with greatness.

In the green room, Martinez, the former Yankees first baseman, signed 15 bases from the game that day, where he had been honored with a plaque in Monument Park. Each base bore a Steiner Sports logo.

“How many bases do you change a game?” Martinez asked.

“Usually twice a game, but every time Jeter gets a hit, we take first base,” Steiner said. “We do everything to commemorate that.”

(More than two months later, Martinez’s scuffed, autographed bases have been discounted to $599.99. Similar ones signed by Jeter are nearly three times that.)

Before the program, the audience watched a vanity video about Steiner’s company filled with tributes from employees and clients. When he took the stage, Steiner greeted the “Yankees premium customers” and briefly experienced a reverie about his fortunate connections. “Yankees. Steiner,” he said. “Steiner. Jeter. Yankees.”

Steiner interviewed Jeter and Martinez for nearly an hour, asking comfortable questions to clients he has known and enriched for nearly 20 years.

Afterward, Jeter and Martinez moved to a separate room where the fans who had paid $2,000 to $2,500 for premium packages met each player, received signed collectibles, posed for photographs with them and attended a cocktail party. As Jeter and Martinez sat together in rigid chairs, fans stood in line and, when signaled, moved behind them for a snapshot.

One Jeter devotee, Jenny Drechsel, left her encounter simultaneously crying and hyperventilating. She had given Jeter a shirt and he had thanked her.

Tara Colandrea, another fan, said, “I want everyone on Facebook to be jealous of me.”

It might have been a perfect night to move the first few rakes, but they are not yet for sale. Steiner said he was waiting until after Jeter’s final game.

On the night of his epiphany, he followed the groundskeepers into their room behind the third base dugout.

“I want all these rakes,” he said to Dan Cunningham, the head groundskeeper. “I’d reorder them with the Yankee logo on it and do it right. There are 20 rakes here. I could get $200 each for them.”

Jeter admitted that he was not surprised by Steiner’s plan when asked a few weeks later.

“I don’t know why anybody would want one,” Jeter said. “But if they wanted me to sign them, I guess I would.”

--

This article originally appeared in The New York Times on Friday, September 5, 2014 and can be viewed at: http://nyti.ms/1lEtxx1